Reproduction of an article by Stephen Anderton, published in SAGA Magazine, August 2005.

All Photographs by Charles Hawes.

What is it about lost gardens that appeals so much? Maybe it’s a Garden of Eden thing, and the longing for lost innocence; surely that is why women of a certain age make “white gardens.” Perhaps it’s just that people like the idea of jungles and mud and mechanical diggers. Whatever the reason, lost gardens are a winner. Look what being “lost” did for Heligan. Now we can see what it will do for Dewstow, a garden in Monmouthshire which is literally coming to light after 60 years underground.

The garden belongs to farmer John Harris and his family. Farmers are not known for their delicacy and sensitivity when it comes to the landscape; they have a living to earn first. But here at Dewstow things are different. Some years ago, seeing that the future of farming was uncertain, not to say unprofitable, the Harris family – John, his father and his brother – developed a golf course on their land, which formed part of the old Dewstow estate.

Ten years ago they managed to buy the other half of the estate to create a second golf course, and in 2000 they bought Dewstow House, a modest farmhouse with classical pretensions. John Harris, his wife and children moved in.

What a view they could have down to the Severn estuary, were it not for mature trees surrounding a couple of the artificial ponds (which of course every ‘lost’ domain must have). But Harris has lived all his life on the estate and it is a landscape already familiar to him. He also knew that the house had once had remarkable gardens.

- Alpine Garden

What he did not know was that there among the trees, overgrown or literally buried, were six acres of interconnecting rock-work pools and a labyrinth of carefully constructed magical caverns running almost under the house. How would an estate agent describe that? Just think of the damp! The garden was made between 1893 and 1940 by Henry Oakley, a director of the Great Western Railway. He was a bachelor with a definite eye for the ladies, but he chose to invest his personal resources in his garden rather than a family. To layout the garden, Oakley employed the family firm of Pulham, one of the great names in garden construction, and famous for the artificial rock-work which they produced over an extraordinarily long period, from the late 18th century unti11940. Their rockwork (cement over brick rubble) was so naturalistic that hundreds of gardens employed them. Modest examples of the company’s work still exist at Audley End, Sandringham, Buckingham Palace, the Swiss Garden, and Waddesdon. Great care was always taken to match the rockwork to the local stone where it existed, sometimes going even as far as inserting separate strata in different colours, and always making the arrangement of rocks appear natural.

Dewstow was an extravagant project even by the Pulhams’ standards. As well as providing a kitchen garden and glasshouses typical of the period, they installed a series of six large pools with a massive pumping system, a woodland ravine complete with gushing stream, a stumpery (an area created with tree stumps) and a huge tropical house. In the sunnier areas they made pergolas and herbaceous borders, and a grand dovecote. You name it, Dewstow had it.

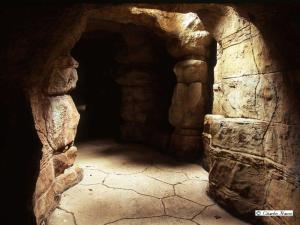

But it’s the work the Pulhams did underground that makes the place so extraordinary. It was a pure fantasy for people and plants, with tunnel systems, caverns and tufa grottoes, some with Italianate fountains, formal pools with balustrading, others dripping with ferns and artificial stalactites. Water flowed from one cavern to the other, often turning the paths between into a series of stepping stones separated by delicate channels of water. Some of the tunnels were almost pitch black, others were lit by glazed skylights. One of the more horticulturally ambitious caverns was lit by a great glass dome above ground.

The cave system weaves around mysteriously in the true manner of a labyrinth, except that it is more heart-lifting than threatening; no Minotaurs here, though the odd nymph might come as no surprise. The obvious route for Henry Oakley was to take his visitors out of the front door, round the corner, and down steps to a bizarre Doric doorway, more like the entrance to a grandiose coal cellar than an underground kingdom. Then he and his guests could enter the labyrinth, steal through its watery caverns where light reflected from the water flickers on the walls, and finally step up into his monumental tropical house.

It is not known whether the garden was designed by Oakley or the Pulhams, but what a feat of imagination it is. It is reminiscent of the Victorian garden at Biddulph Grange in Staffordshire, where tunnels connect a ‘Scottish Glen’ of pines and heathers to the willow pattern landscape of ‘China,’ complete with a temple and red lacquer bridge. It could be a kitsch miniature of the awesome, 18th-century hilltop tunnels at Hawkstone Park in Shropshire. It has echoes of the tunnelled and temple-riddled, fire-spitting rock-work ‘Island of Vesuvius’ on the lake at Worlitz near Dessau. (Worlitz is a landscape garden every bit as ambitious as our Stowe, and this September, after many years of restoration, ‘Vesuvius’ will erupt again for the first time since 1800.)

When Oakley died in 1940 succession to the title of Dewstow became uncertain, and eventually the property was sold. The above-ground parts of the garden and ponds were largely filled in, being seen as uneconomic in post-war Britain, and the cavern system, like some royal tomb, was blocked with soil. The burial continued: in the 1960s yet more soil from the construction of the M4 was dumped over the Pulhams’ work until little of the garden remained visible. Then the Harrises arrived.

How do you start? As parts of the garden came to light, Harrises of two generations held a family conference and, as life-long Dewstow-lovers, decided there was no option but to restore it. Since then there have been extraordinary discoveries and a huge amount of repair work has been undertaken – the ‘golf dividend’ has opened the tomb.

Pools have been emptied of soil and relined, and new pumping systems installed. Even the moss-covered fountains in the caverns are flowing again. Walls, balustrades, paths, rockwork and ‘stalactites’ are being carefully repaired. Temporary roofs have been placed over some of the fern caverns. A barn which has an asbestos roof supported by ornate cast-iron pillars – Oakley’s vast tropical house – is having its concrete floor removed and is once again connected to its underground tunnels.

Harris employs a staff of four on the garden, and the project has already cost him a fortune. The money has all been his own since, as is so commonly the case, the terms for financial assistance from official conservation bodies made the project too expensive to undertake their way. Ironically, while Harris has been unearthing the garden at his own expense, it has been awarded Grade I status on the Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in Wales.

The historian Claude Hitching, who is researching for a book on the Pulhams, calls Dewstow “the jewel in the crown” of their work and a very large project by their standards. But even he knows all too little about the Dewstow work. Five of Hitching’s ancestors worked for the Pulhams, and he is frustrated because the Pulham records were destroyed in the 1940s: “A list of clients for whom they had built rock gardens and ferneries was published in 1877, but thereafter it is still all speculation,” he says.

Harris still displays that admirable, matter-of-fact farmer’s manner when it comes to the garden’s future.

“We’re just plodding on. We’re putting back what we can, as and when we can,” he says. His gardeners are busy replanting above and below ground, to put back some colour and decoration on the garden’s bones. Down below, where it’s virtually frost-free, there are hardy ferns, not-so-hardy Boston ferns and stag horn ferns, air plants, spider plants, creeping little Ficus pumila and even a banana. Beside the surface ponds there are phorrniums, Joe Pye weed (Eupatorium purpureum), and many a fashionable perennial. This is no like-for-like replacement of period plants, but then there are no extant plans to say what was here anyway.

Instead the garden is a family affair, and Harris still lives in the middle of it; it’s a wonderful playground for his family (the niches in the tunnel walls are full of little night-lights). But he also opens it to the public for guided tours by appointment.

If Harris can only keep the garden moving forward, staffed, and can see through the repairs, then we shall all be the richer for it. There is still plenty waiting to be done: what will lie under the concrete farmyard behind the house, for instance? No one has a clue, except that it’s bound to be fascinating.

Dewstow Hidden Gardens and Grottoes, Caerwent, Monmouthshire, 01291 430444, http://www.dewstow.com. Guided tours only.

Charles Hawes Photography – charles.hawes@gmail.com

This design is steller! You most certainly know how to keep a reader entertained.

Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start

my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Fantastic job. I really

enjoyed what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it.

Too cool!